Liturgy 35.2: Liturgy and Identity

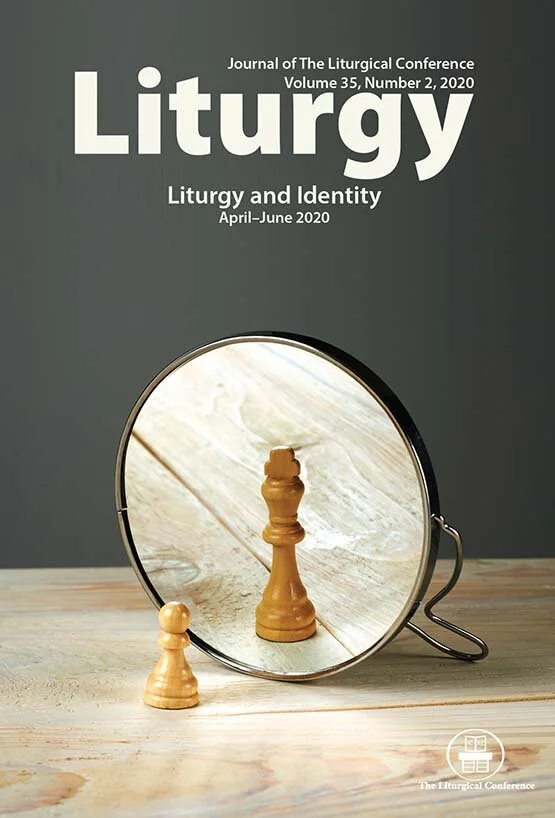

This issue of Liturgy deals with “Liturgy and Identity.” What follows is an excerpt from Guest Editor Matthew Lawrence Pierce’s “Introduction” to the issue. We hope this will help define the theme and encourage you to want to read the entire issue.

~~~

The essays in this issue of Liturgy focus on worship as a tool for negotiating individual and collective identity. Ethicist Kwame Appiah has several salient observations about identity that are germane to the theme of this issue of Liturgy. He writes that “identities come, first, with labels and ideas about why and to whom they should be applied. Second, your identity shapes your thoughts about how you should behave; and third, it affects the way other people treat you. Finally, all these dimensions of identity are contestable, always up for dispute: who’s in, what they’re like, how they should behave and be treated.”2 Thus, “identity” here is not understood as a singular, stable notion of the self, but—as with King David—often plural, with different “labels and ideas about why and to whom they should be applied,” how one thinks one should behave, how others treat you, and how individuals and communities navigate contested identities.

In “Redeeming a Spoiled Identity,” Peter Schuurman describes how an Anabaptist megachurch employs an annual ritual event to distance itself from the other evangelical communities and other megachurches. Drawing upon the sociologist Erving Goffman, Schuurman provides a theoretical underpinning for thinking about identity in relationship to others, noting that “who people are is a construction of social perceptions and roles people take and shape over time. Individuals don’t exist or have identities apart from being persons-in-relationships; identity is effectively a collective production.”

“Sent as Host and Guest in Little Mogadishu,” by Jane Buckley-Farlee, highlights some of the transitions faced by individuals and religious communities that find their identities called into question. A white Lutheran pastor, she offers an insider’s perspective on how the changing demographics of a neighborhood require a congregation and its pastor to revisit their role within the community and their understanding of self. When the congregation and its pastor were members of the neighborhood’s religious and ethnic majority, they played the role of “host” within the community. As they became religious and ethnic minorities in that neighborhood, the congregation had to negotiate dual identities as both “guest” and “host.”

Though a remarkably different context than “Little Mogadishu,” “Young, Restless, and Liturgical” by Winfield Bevins nonetheless examines how another group of Christians—young evangelicals—have grown ill-at-ease in their home tradition. Drawing upon the research for his book Ever Ancient, Ever New, Bevins explores the reasons why some young evangelicals have turned toward more “liturgical” expressions of worship.3 In the choice of more “ancient rhythms of liturgy,” these young people have sought a new spiritual identity as well as a greater sense of authenticity, belonging, and purpose.

In “Social Critique as Religious Formation,” Jack Delahanty shows how two liturgical practices—lectio divina and personal testimony—foster spiritual growth and collective religious renewal within faith-based community organizing. Though undertaken outside of their original contexts, these “relational practices” provide religious participants in community organizing with a means of connecting their activism to their faith and bridging racial and cultural lines among participants.

In “Unity and Diversity,” David Williams illustrates how liturgical practices both united and then divided the Seventh Day Adventists. Early Adventist hymnology sought to bolster and express the denomination’s commitment to Jesus and the centrality of his return. When the multiracial denomination is compelled into segregated worship settings, that shared hymnody and the faith it expresses come to take on new, racialized meanings.

Teva Regule provides a glimpse into the liturgy as identity formation in her examination of “The Mystagogical Catecheses of Cyril of Jerusalem.” The catecheses illustrate an important dynamic in the relationship between liturgy and identity precisely because they were delivered after catechumens had undergone the rituals. Regule thus provides an example of how a ritual blended with instruction might serve as means of crafting a new identity.

Drawing upon ethnographic research on Midwestern Eastern Orthodox in “Windows into Heaven,” Daniel Winchester explores how the Orthodox employ icons to shape their communal and individual identities. Visually prominent within the worship and yet portable enough to hang from a rearview mirror, icons place worship and devotional practice within a set of relationships that “span the divides between life and death, heaven and earth,” including the figures depicted within the icons, those who give icons to others, and to individuals for whom icons come to serve as prompts for introspection.